February 14, 2015

Wickwire love letters on display

Bob Ellis/staff photographer

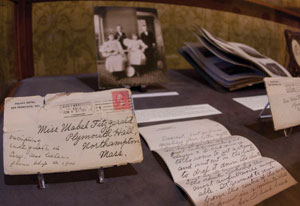

Letters written by Charles Wickwire Sr. to his girlfriend, Mabel Fitzgerald, who would later become his wife, are currently on display at the 1890 House Museum.

Megan Eves said 1890 House Museum officials don’t have any diaries or journals from the Wickwire family.

“You don’t get that feeling that they are a real family,” she said, even though, as museum coordinator, she’s explored the 37 Tompkins Street, museum, peering at its cutlery, parquet floors and chandeliers.

But now, a series of letters written in the late 1890s and early 1900s, bring the Wickwires, headed by Chester Wickwire, a founder of the Wickwire Bros. factory in Cortland, to life.

“These letters are a window to (their) every day lives,” said Eves.

“The Art of the Letter — Correspondence in Victorian America,” is an exhibit of Wickwire family letters in the 1900s at the 1890 House, 37 Tompkins St.

The exhibit, which has a love theme in honor of Valentine’s Day, can be seen through March 5. The museum is open noon to 4 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays.

Fourteen letters comprise the exhibit. One set is between Charles, son of Chester Wickwire, who built the 1890 House, and his sweetheart Mabel Fitzgerald, who lived next door.

The other set is correspondence between Ardell Wickwire, Chester’s wife, and their son, Fred Wickwire.

Actual letters, as well as family photos, are situated in glass cabinets with portions magnified to poster size. Letters are also available for perusal in printed copies. People can also see the accroutraments of writing, stationary, pens and papers and post cards of the time. Also, three mannequins with women’s dresses in winter wear add to the exhibit.

Charles was employed in the family business, a manufacturing plant that made metal mesh and put Cortland on the map. He frequently traveled across the country, as well as to Europe, and he wrote to Mabel, whom he later married. But Mabel, it appeared, rarely wrote him back.

“We don’t have any of Mabel’s letters,” said Meghan Aagaard, assistant museum coordinator.

But she did save his letters, she pointed out.

“The last letter I have from you was written the 23rd of May,” Charles writes Mabel on June 4, 1899. “Such a long time ago. I don’t think you are very nice, not to write to me more. You knew I would be here anyway until the last of May. I do hope I will get one in Portland.”

Charles would start his letter out: “Dearest.”

“Dearest, I wish someone would write to me like that,” said Eves. “She should have written to him more.”

Eves thinks Mabel was preoccupied with her life at Smith College, hobnobbing with her friends.

“Charles was traveling on his own. He was in a work mindset, traveling to places. He loved her so much,” she said.

Ardell Wickwire wrote to her son, Fred, who was at boarding school at Phillips Andover Academy.

“Those are a lot of fun to read,” said Aagaard. “Ardell is doting. She would remind him to wear sweaters and go to church.”

And she chastised him constantly for not writing back.

Several books on letter writing were published at the time, said Aagaard.

“There were a lot of rules, ... What type of paper, what type of ink, what was proper to mention in a letter,” she said.

“Victorians are notorious for their procedure,” said Eves.

Kathryn Thomas and Maggie Romanowski, two SUNY Cortland interns, archived the letters while Lacey Ryan, a SUNY Binghamton student, transcribed them.

“There was a fine art to letter writing,” said Eves. “Today to write a letter ... is something most of us don’t do any more. It’s a personal thing.”

To read this article and more, pick up today's Cortland Standard

Click here to subscribe